¶ 16 million is large number. It is used by Philips to promote their smart or intelligent lighting system Hue. The system was launched in 2012, and is one of several smart home-lighting systems. The system offers 16 million colours to choose from when you configure their light bulbs or lamps.

¶ With products like Hue, the world of domestic lighting has become more complex. The customer get more varieties and opportunities to design lighting experiences and atmospheres than before. This however doesn’t mean that lighting or light design was something banal before. Electric lighting has always been more than the flick of a switch, more than mere button-pushing [1].

¶ The mundanised systems of electrical lighting is based on extensive infractructures and operations. In their employment of this infrastructure, people use light in often creative ways. Meanwhile they also depend on certain norms and unwritten standards, something anthropologist Mikkel Bille has pointed out in several projects. Lighting is more than technology with an aesthetic dimension, it should be understood as a deeply cultural and social phenomenon [2].

¶ When the 16 million colours are introduced in the marketing of Hue and in the offerings to customers, there are more choices and configurations to consider than ever before. The question is what this large number and choices might mean? Has domestic lighting become more advanced, more of a craft now?

¶ The number 16 million show what is possible. It also hints at the complexity and a proposed ingenuity of the system. But when it comes to using the system, the complexity is also combined with simplicity. Within digital cultures, a common way to navigate a system with a multitude of variations is through presets or templates. Some of these presets Philips have chosen to call Light Recipes. When they promote their recipes, they can use the large number of colours as the starting point to evoke imaginaries about lighting and the use of the Hue-system as a craft or science. This is how the light recipes are described:

Did you know… That our Light recipes (Relax, Read, Concentrate and Energize scene) are specially selected based on the knowledge from years of lighting research? By setting your Hue lights on a high color temperature like the Concentrate and Energize scenes you can reduce sleepiness and increase your alertness and concentration levels. While the Read scene gives you the perfect amount of light to read a book, the Relax scene helps you to wind down.

https://labs.meethue.com/news/get-back-into-the-swing-of-things-as-summer-comes-to-an-end-with-hue

¶ Here the system is promoted as advanced and as based on scientific knowledge and competencies. This is the hallmark of the smart home-ethos. The user has distributed smartness to systems that deliver through an obfuscated complexity. In the background, 16 million colours. At the front, scientifically crafted recipes. Like a mix between a medical precription offered to you by a professional doctor and a set of instructions given to you so you could achieve that perfect serving.

¶ Let’s compare the Hue lighting experience to another automated experience. In one of the lunch rooms of Lund University, there’s a coffee machine. For some time it had a sticker attached to its front. It promoted the product by stating that the coffee from the machine had over 800 aromas. The number recur throughout a number of coffee-related places, such as artisan coffee outlets and other organisations dealing with coffee.

¶ The number stems from sources stating that 800 discernible chemical compounds or components can be produced through the coffee making process. Roberto Zironi, professor of Food Industries at the University of Udine and chair of the scientific committee of the International Institute of Coffee Tasters write about the complexities of coffee aromas:

Coffee is a drink that expresses most of its sensory characteristics in its smell and its aroma. The aroma is the sensory characteristic resulting from a combination of smells contributed by the chemical substances and by their intrinsic synergies and is the result of high-quality raw materials and of technological steps for the processing of the green matrix into roasted coffee which are thoroughly carried out. It is important to point out that the aromatic precursors are already present in the green bean which, exposed to roasting, develops new substances that contribute to the complexity with more than 800 volatile components found in a cup of coffee.

http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/the-markers-of-non-quality/06/

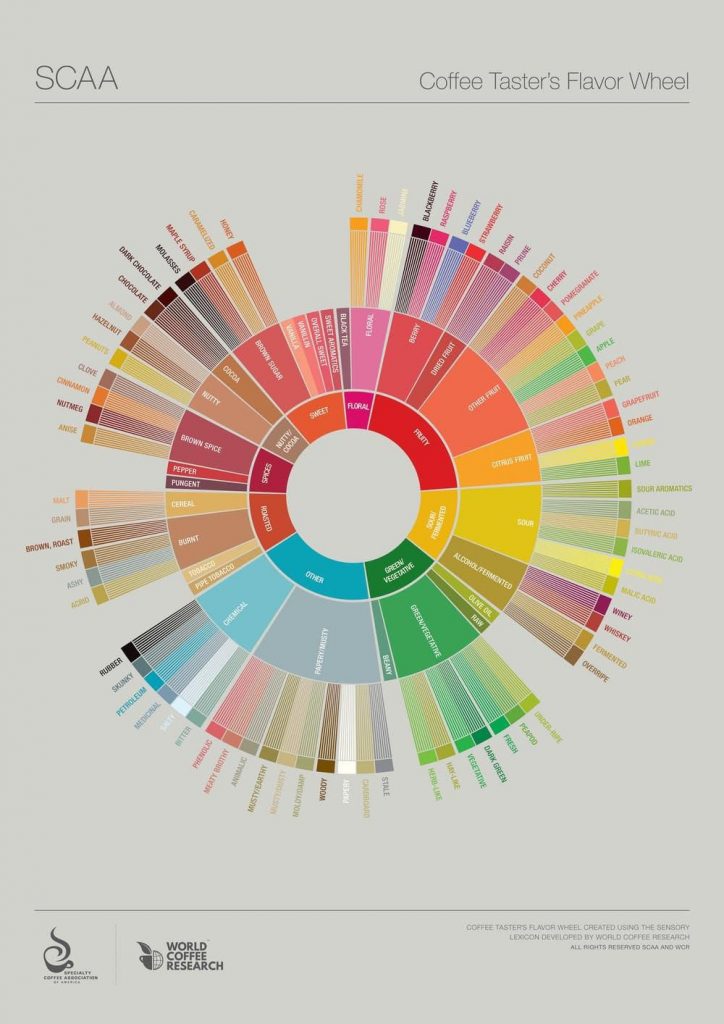

¶ 800 volatile components signals some requirements when it comes to coffee making and the raw material and equipment that is used. High numbers might require skill or good technologies. The complexities and sophistication of coffee is also symbolised through the Flavor Wheel, a resource for the coffee industry to provide a common vocabulary for sensory qualities and flavor of the beverage.

¶ The Flavor Wheel is a way to visualize and organise something as ephemeral as taste, aroma and flavour. The many categories together with the statement about 800 aromas or chemical compounds give a certain aura around coffee. According to Christopher H. Hendon:

Coffee is unique among artisanal beverages in that the brewer plays a significant role in its quality at the point of consumption. In contrast, drinkers buy draft beer and wine as finished products; their only consumer-controlled variable is the temperature at which you drink them.

Hendon, Christophen H. (2017): Brewing a great cup of coffee depends on chemistry and physics. In: The Conversation.

¶ This statement ignore the context and circumstances in which a drink is enjoyed (or consumed). It is worth noting that the 800 aromas or flavours can be used to promote not just coffee making as a sophisticated craft, but also coffee generated automatically by products like a coffee machine, as in the lunch room at Lund University.

¶ What can we learn from comparing coffee making with domestic lighting systems like Hue? First, it might point towards the dynamic between skills/knowledge and automation. When is something more or less artisanal and when is it automatic? What is the meaning, the qualities and risks of technological assistance?

¶ One way to deal with large numbers is to limit the number of choices. As mentioned, a common way to do this within digital culture is through presets and templates. These are also controversial, especially among creatives that might see them as cheap gains. Something achieved without “real” knowledge, using simple technological aid. However, as algorithmic assistance, machine learning and automated customisation become more widespread, presets and templates become hard to avoid. They are also a remedy for configuration fatigue, the exhaustion caused by the requirement to configure yet another system or service.[3]

¶ Then there are the numbers. 800 aromas might be a whole lot to deal with when making or consuming coffee. 16 million colours of light is also a lot to handle. It is a large number. Something that might evoke reactions, emotions or fascination. Large numbers are words used to define extremely high amounts of something, million, trillion or centillion. The numbers are often beyond human experience or comprehension. What is even 16 million colours? Or a centillion. Within sciences such as mathematics the words are not used that often, instead the numbers are written using scientific notation like 10303 (centillion).

¶ The connection between numbers and human experience is intricate to say the least. How do you experience amounts of flavours, colours, km/h (mph) or the metrics of a space? As historian and philosopher Helen Verran has put it: ”’Numbers’ is the name of a vague and sprawling category. A ragged hold-all for a conceptually multitudinous set of things that are done or performed differently in myriad times and places.”[4].

¶ Large numbers often occur in relation to advanced technologies. The incomprehensible architecture of data streams, of software and networked infrastructures, is sometimes described with numbers. The entire bulk of software required to run Google’s operations in 2015 were estimated to use 2 billion lines of code. As a comparison, Microsoft Windows was at the time based on (merely) 50 million lines. What does this mean? Is it even meaningful to count lines of code?

¶ What is interesting is how these complex systems, somewhat defined by ungraspable large numbers, become the prerequisites for mundane and even banal everyday actions and routines, such as unenthusiastic browsing, clicking and scrolling through contents on a screen. Actions that in themselves generate big data streams that are fed back into the system as fodder for further analysis or calibration of the apparatus.

¶ When Larry Page and Sergey Brin founded Google in 1998 they tapped into the potential of large numbers.[5] When choosing the name for the operations they were about to start up they stumbled upon a large number. In a lecture in 2003 Larry Page explained how it happened:

“We built a whole ranking system for Internet sites,” he said. “We accidentally created a search engine.”

Brin and Page initially named their creation BackRub, based on its ability to analyze the “back links” to a Web site.

“But we realized BackRub wasn’t the world’s greatest name,” Page said. Instead, he and Brin looked through Web sites and URLs before finally stumbling across a list of very large numbers. The word “google” was at the top.

A friend later pointed out, however, that the number is actually spelled “googol.” But the misspelling had two o’s and ended with ‘le’ so they decided to stick with it, Page said. Plus, the Google domain name was still available.

A googol is the number one followed by 100 zeros. According to the Google Web site, “There isn’t a googol of anything in the universe. Not stars, not dust particles, not atoms.” The name reflects Google’s mission to organize the limitless amount of information on the Web.

Hanley, Rachael (February 12, 2003). “From Googol to Google”. The Stanford Daily. Stanford University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

¶ It is bewildering that the name of one of the world’s most powerful corporations can be derived to a spelling mistake. Large numbers combined with sloppiness. A combination worth pondering on for a while. The way errors are defined, managed and eventually corrected have characterized the development of search engines and the architectures in which they are embedded, something that Rachael Hanley bring up in an article about a lecture by Larry Page at Stanford in 2003:

One of the challenges of creating a useful search engine for a wide range of users is being able to account for human error. To demonstrate, Page used the example of one of the most popular searches on Google: “Britney Spears.” Page displayed a list of the hundreds of ways people had spelled the singer’s name, ranging from “Brittany Speers,” to “Britney’s Spear” and even “Prittanay Spearese.”

“It turns out that most people misspell some things,” said Page, who confessed that he also had trouble with spelling. Misspelled words cause huge problems for search engines, he said. “You end up finding documents with misspelled words, which is not really what you wanted.”

To compensate for spelling mistakes, Google now suggests the proper spelling for many common words, from “Britney Spears” to “environmental.” In the future, Google may be able to do even more, Page said. An ultimate search engine, Page said, could even be considered artificial intelligence.

“The ultimate search engine is something as smart as people — or smarter,” he said. “For us, working on search is a way to work on artificial intelligence.

Hanley, Rachael (February 12, 2003). “From Googol to Google”. The Stanford Daily. Stanford University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

¶ Artificial Intelligence and machine learning has indeed started to become integrated in the assemblages involving search engines. It has contributed to algorithmic auto-correction becoming one of the most mundane and important technologies of the early 21th Century. This is how large numbers and everyday routines are combined to nudge users into position or sending them off in different directions. Large numbers and small actions. A wedding between the arcane and the banal. Welcome to Auto-correct Society.

[1] There is nothing banal about button pushing either. In her book Power Button. A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing (2018) Rachel Plotnick show how digital (referring to digit, the synonym for finger) commandment can be connected to several political and social aspects of modern and industrialised societies.

[2] Bille, Mikkel (2019). Homely atmosphere and lighting technologies in Denmark: Living with Light. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

[3] In the article Enhancement or Distortion? From The Claude Glass to Instagram (2013), in Sarai Reader 09: Projections I deal with the ways technological tools have been debated in relation to visual culture. It is also a theme that recur in relation to the technological button pushing that Plotnick has written about (see note 1). This very site is by the way based on a preset, the WordPress Twenty Twenty-theme. It is highly intentional. The Twenty Twenty-theme, the (perfect) choice in a world where 2020 has got a very special charge. Numbers are charged through the things they come to define. 13, 1945, 2000, 9/11, 666, 100 (%), 24/7 or 2020.

[4] Verran, Helen (2018). Decomposing numbers. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 8(1–2), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/698356

[5] For an extensive analysis of the way search engines are integrated in people’s everyday life, see: Invisible Search and Online Search Engines. The Ubiquity of Search in Everyday Life (2019) by Jutta Haider and Olof Sundin. In the book they use mundane-ification, a word that sounds similar to mundanisation, to propose how searching became de-professionalised and inserted into all kinds of social practices (p. 2-3). However, they do not further develop the concept theoretically in relation to media theory or studies of emerging technologies.