¶ When catastrophe happen in fiction, it is often dramatic. It comes as a sudden event. The Netflix-series The Rain (2018) is about a virus, spread through rainfall. It all starts in Copenhagen. The series is full of alluring ruin footage, simultaneously beautiful and horrifying. A postapocalyptic Greater Copenhagen Area. The infrastructure, so familiar for the ones living in the region, demolished, abandoned, ruined.

¶ The Rain is like a dark mirrorworld of the Corona-world. The oneliner in the trailer: ”You never know when your world is about to change”, bunkers, isolation, a killing virus, civilisation wiped out. The usual formula of postapocalyptic thrillers. Everything twisted into dramatic terror and bombastic disaster.

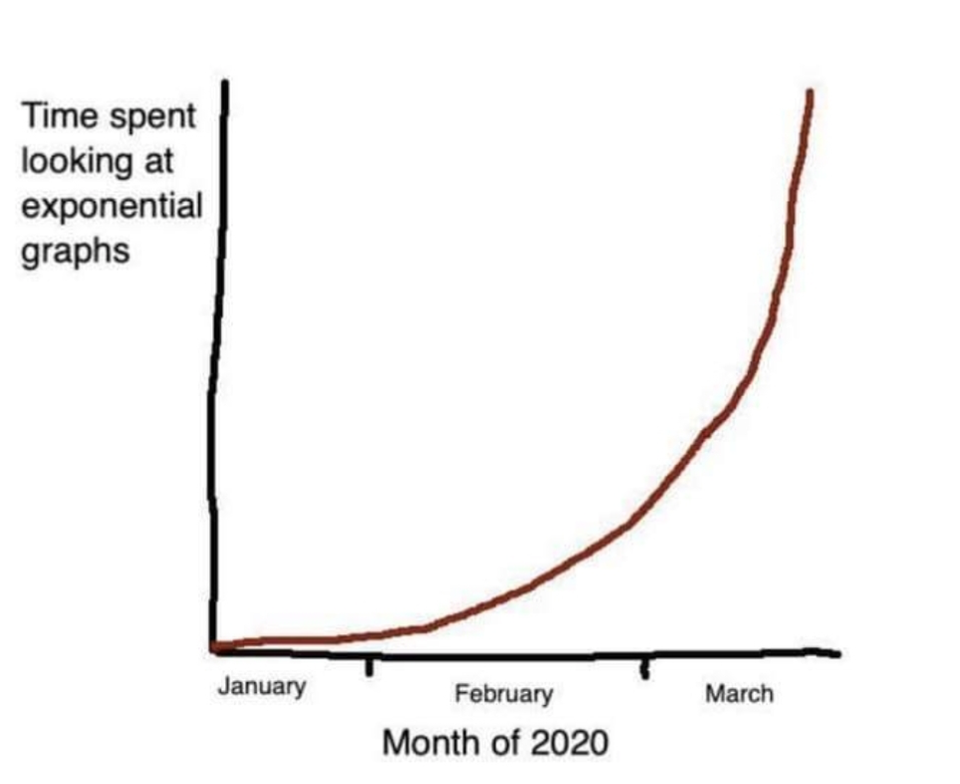

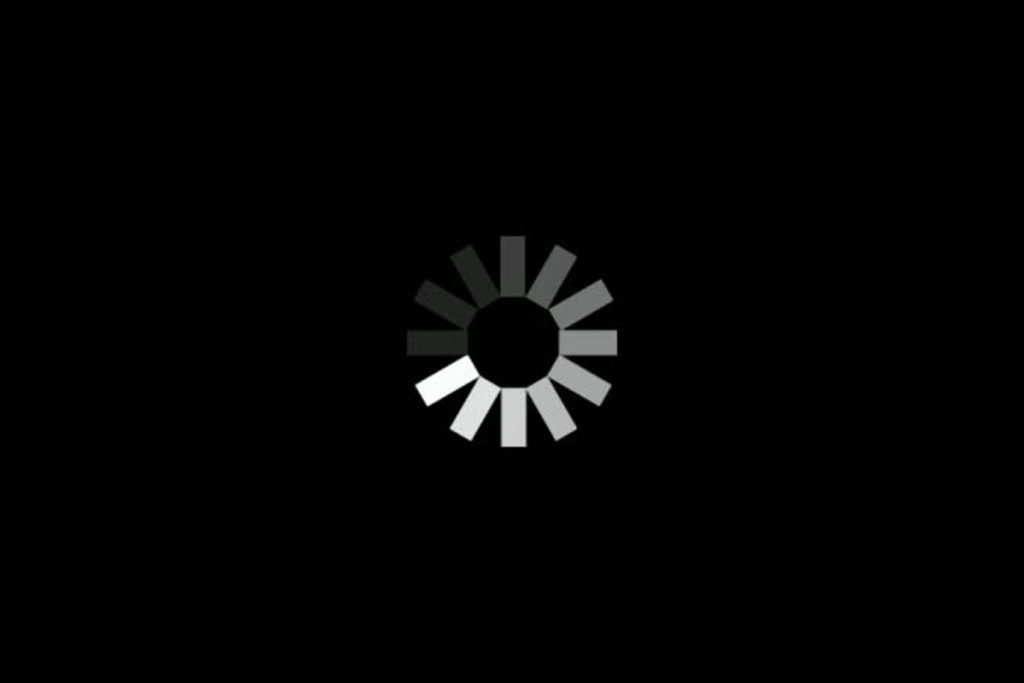

¶ The occurrences around COVID-19 were dramatic, to some extent. But for many people, not immediately struck by the virus or its chain reactions, life was characterised by slowness. Everyday life had changed, but most of the change seemed to take place somewhere else. People stayed at home, in ”the small world”. Waiting for events. Looking for signs of a coming change. Surfing curves and evaluating prophesies. Listening to the pleas from authorities, pleas for collective discipline: Follow rules and recommendations. People were trying to comprehend Lock-down society or the metrics and practices of social distancing. Associations to war-time were evoked. But the front was ephemeral, somewhat manifested in the Intensive Care Units in hospitals, the healthcare workers being the heroes of confined worlds. The catastrophic was lurking like an undertow running below the mundane. Drama was hinted at in the news. A liminal state, waiting, a state of buffering.

¶ Buffering occur while a stream of data loaded in advance of a rendered online-video is choked. As a watcher you are forced into a state of waiting, while the flow of events in the video is paused.

¶ Buffering is the digital technological equivalent of the philosphical concept becoming, a state through which humans are not merely being, but all the time becoming. Humans are becoming through living, experiencing, perceiving and thinking together with the things of the world, immersed in a continous flow of impermanence and flux.

¶ Anthropologist Tim Ingold, drawing on philosphers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, have contemplated on the way that humans live life as a kind of go-along or entanglement together with things, materialities and various entities. “To know things you have to grow into them, and let them grow in you, so that they become a part of who you are”[1] This is a transformative process, a process of self-discovery/learning about things and the world. You learn and become who you are through cohabitation with things and entities.

¶ Sociologist Deborah Lupton, when writing about the ways people live with the data that is generated by them, expounds on Ingold’s approach by stressing that he:

…contends that material artefacts are never fixed or completed. Because they are open to new meanings and uses, they are always in a process of becoming something else. As they move into new or different contexts, artefacts change in meaning, even if not always in shape.[2]

¶ When living with networked digital technologies, the process of becoming is conjoined with the properties and manifestations of the technology. One such property is buffering. A feedback loop might occur between human becoming and technological buffering. A movement along with technology, through which human lingering is conjoined with technological buffering.

¶ Buffering is a major theme in author Tom McCarthy’s novel Satin Island.[3] The novel is an intriguing account of the life of a corporate anthropologist during the 2010’s. The protagonist U., with a background in university-based anthropology, has left academic life to work in a corporation. He’s doing applied or corporate anthropology. The book delivers some good and quite witty analyses of anthropological practice in a corporate world:

What does an anthropologist working for business actually do? We purvey cultural insight. What does that mean? It means that we unpick the fibre of a culture (ours), its weft and warp – the situations it throws up, the beliefs that underpin and nourish it – and let a client in on how they can best get traction on this fibre so that they can introduce into the weave their own fine, silken thread, strategically embroider or detail it with a mini-narrative (a convoluted way of saying: sell their product).

Satin Island. page: 20-21.

¶ U. works on an extensive and open-ended-project called “The Great Report”. Inspired by early anthropologists, especially Claude Lévi-Strauss and dreams about the combinatory and general intellectual work of polymaths such as 17th and 18th Century Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, U. tries to find a secret logic behind the overwhelming flows of data, information and goods in the world. He formulates something called Present Tense Anthropology.[4]

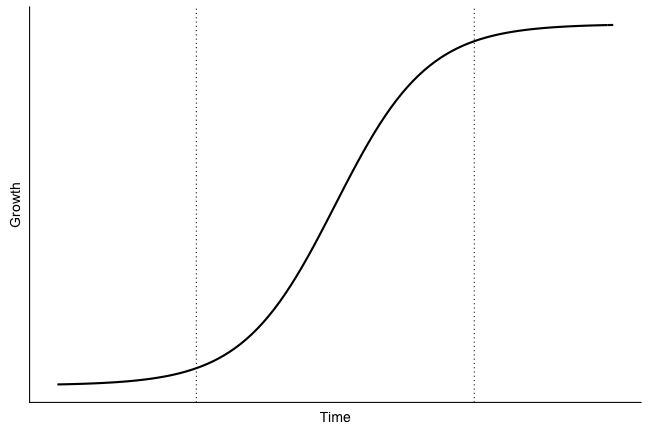

¶ Through Present Tense anhropology U. collects a wide array of stories and vignettes about everything from oil spills to dead parachuters. But all the time, the endeavour is characterized by a kind of preparation for something, a kind of lurking anticipative atmosphere, a state of suspension, buffering.[5] The growing diverse collection of material for The Great report is there as potential seeds, from which narratives could sprout. But not quite yet.

¶ This mindset, through which all actions and experiences are lived while preparing for how the experiences can be presented for others in the future, characterize the novel. A mindset or a kind of social media-ethos, through which experiences are always lived in a reflexive state aimed at potential future Instagram-posts or Tweets. Provisional renditions. Mundane suspension. Material collected and composed to eventually be used in the future. An uncertain future.

¶ Buffering also characterized Corona-2020. Now it was at a large scale, societal, collective level. The overwhelming flows, the wide-ranging mobility of airports and bustling tourist sites from the Satin Island-novel had been brought to an almost standstill. Instead of flow and mobility: Buffering.

¶ The real action taking place in caring units and among people fighting the virus or handling the collateral damage. Or in the improvisatory work of organisations that hastily had to reorganise. Preparing for the worst, while hoping for the best. In the obfuscated work taking place beneath the surface, beyond grasp in datacenters, in the electronic circuitry, and among often neglected sectors of service- and maintenance-work. For many people, the crises meant enormous stress and arduous work. Except that: buffering.

¶ Waiting or buffering can be especially charged when living in a society characterised by “change imaginaries”, by rapid change, speeed and expectations of instant delivery. In the book The Secret World of Doing Nothing, ethnologists Billy Ehn and Orvar Löfgren make an extensive analysis of the role of waiting, impatience and boredom in Western culture. They argue that:

It is difficult to know if we wait more or less patiently than people did in earlier times, but in an era where “time is money” and where we have become accustomed to immediate gratification any wait can feel as if one had been waiting “for an eternity.” The modern landscape of impatience takes on emotional charges–irritation, restlessness, anxiety, boredom, and longing–as well as evokes ideological debates.

Ehn, Billy & Löfgren, Orvar (2010). The Secret World of Doing Nothing. Berkeley: University of California Press. page 209.

¶ Waiting is something humans always have done, but the way it is experienced, imagined, discussed and handled varies depending on time, space and context. During the Corona-crises waiting got its special characteristics. In debates and discussions the frustrated question about “how long will this last” was recurrently asked. What are we waiting for? What is the prognosis, how does the curve look, what does the experts say?

¶ The buffering-state is a construct, whose techno-organisational underpinnings have to work to keep the circle spinning. Or, buffering will turn into a full stop. But when it works, when the societal buffering-circle spin, we are in a digitally engendered state of preparation and premediation. Waiting for some eventful future.

[1] Ingold, Tim (2013) Making. Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge. Page 1.

[2] Lupton, Deborah (2018). How do data come to matter? Living and becoming with personal data. Big Data & Society, 5(2), 205395171878631. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718786314

[3] McCarthy, Tom (2015) Satin Island. London: Jonathan Cape. See also: Devin Thomas O’Shea’s Buffering in Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island. He reflects on Satin Island, buffering and the role of literature and novels in an age of abundant data. He also connects the organisational world of Satin island with Franz Kafka’s The Trial in a convincing manner.

[4] McCarthy was inspired by anthropologist Paul Rabinow and his work (together with Marcus, Faubion and Rees) on methodology in eg. Designs for an anthropology of the Contemporary when writing the novel).

[5] Satin Island evoke a scenario where the protagonist is influenced by the mediations and technologically engendered logics of the (present) world. It has some interesting parallells to the novel Television (1997) by Jean-Philippe Toussaint.

The novel Television was published in French in the 1990’s, and it is a humorous account of that time and of the meaning of TV, when Internet-driven streamed moving media did not yet exist. This is how the novel was described on the cover of the English translation:

The amusingly odd protagonist and narrator of Jean-Philippe Toussaint’s novel is an academic on sabbatical in Berlin to work on his book about Titian. With his research completed, all he has left to do is sit down and write. Unfortunately, he can’t decide how to refer to his subject Titian, le Titien, Vecellio, Titian Vecellio so instead he starts watching TV continuously, until one day he decides to renounce the most addictive of twentieth-century inventions. As he spends his summer still not writing his book, he is haunted by television, from the video surveillance screens in a museum to a moment when it seems everyone in Berlin is tuned in to Baywatch. One of Toussaint’s funniest antiheroes, the protagonist of Television turns daily occurrences into an entertaining reflection on society and the influence of television on our lives.

https://books.google.se/books/about/Television.html?id=BRcd1VJIzsoC&redir_esc=y

In Television, the protagonist has stopped watching TV to be able to write his PhD about Titian. It becomes a time of procrastination in Berlin, a suspended state, influenced by the receptive condition induced by the TV. In a review in New York Times, Joy Press describe how procrastination is justified by the protagonist:

…the narrator spews hilariously elaborate justifications for his avoidance of work, at one point bragging that he has, “in a spirit of scholarly scrupulousness and perfectionism, maintained myself for nearly three weeks in a state of perpetual readiness to write, without taking the easy way out and actually doing so.

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/02/books/review/television-le-boob-tube.html

TV-induced stalling and receptive readiness. This can be considered a predecessor of the Internet-media-induced buffering-state of Satin Island and of the atmosphere of Corona Lock-down in 2020.

Version History

v. 1.01 June 1 2020. Minor language fixes.

v. 1.02 June 15 2020. Minor language and typographic fixes.